The Struggle for Democracy in the Democratic Party

There’s a fixation, in online political debate, about voting in federal elections held every two years. Liberals tend to lash out at progressives or independents who suggest they might not vote for Democratic candidates. So much political oxygen gets taken up by the debate over Biden-vs.-Trump.

Voting becomes an obsessive focus because Democratic Party leaders fight efforts to create official channels where changes to policy, like U.S. support for Israel’s war on Gaza, can be openly debated and formally considered. Free technology tools and meaningful deliberation programs that would increase participation within the party, often called “liquid democracy,” are unused.

There’s little discussion on MSNBC, Pod Save America, or in New York Times op-eds about practical ways the Democratic Party could increase participation among its members in the here and now. By keeping such reform options in the dark, party leaders succeed in keeping them off the table.

Even in the age of social media, the Democratic Party remains a stubbornly closed-off enterprise. At the top, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) is a private corporation, as opposed to a membership organization like a labor union, and its leaders have impunity over how they set and enforce party rules. For decades, DNC insiders have gone to war to prevent basic transparency and grassroots reform efforts from gaining steam.

Progressives, leftists, and independents have few mechanisms for registering dissent within the Democratic Party’s obscure committees, or for compelling a public response from its officials. The online shouting matches over presidential elections means the party’s leaders remain insulated from more regular accountability to state members. The party platform remains non-binding, and not even genuinely controlled by DNC delegates.

For the past decade, party leadership’s record has been uninspiring: under the Obama administration, Democrats lost control of both chambers of Congress, the Electoral College in 2016, and a net total of 13 governorships and 816 state legislative seats, the largest state electoral losses since the Eisenhower era. Its D.C. leaders still revolved to lucrative consulting jobs for giant corporations.

Here’s what some DNC reform steps would look like in practice. In November 2020, over 40 members of the DNC—individuals largely elected, or else appointed, by their state parties—signed a public letter to the incoming Biden-Harris political team requesting a dialogue on advancing reforms to empower down-ballot organizing efforts.

- To reduce the influence of at-large members, frequently corporate-tied insiders appointed by the DNC chair, they sought the ability to vote individually on at-large nominees.

- To increase transparency, they proposed releasing a public list of DNC members, publicizing meeting dates, and recording written votes by DNC committees.

- To evaluate spending practices, they proposed making the budget available to members on a monthly basis.

The reform proposals were not advanced by Chair Jaime Harrison and top DNC committees. The DNC expects the full faith of voters when the company won't show its financials, internally, to a DNC member who's served for three decades.

Meanwhile, inside the Biden White House, the corporate-tied Jeff Zients was tapped to be chief of staff early last year. Top political advisor Anita Dunn, of corporate consultancy SKDK, has numerous conflicts of interest with corporate giants. Ahead of a sure-to-be-heated Democratic National Convention in August, President Biden has spoken out against anti-war protests that have the support of the College Democrats of America, an arm of the party. (The size of the movement to vote “uncommitted” in the Democratic Party presidential primaries, as a protest of U.S. policies around Israel’s war in Gaza, surprised many D.C. figures.)

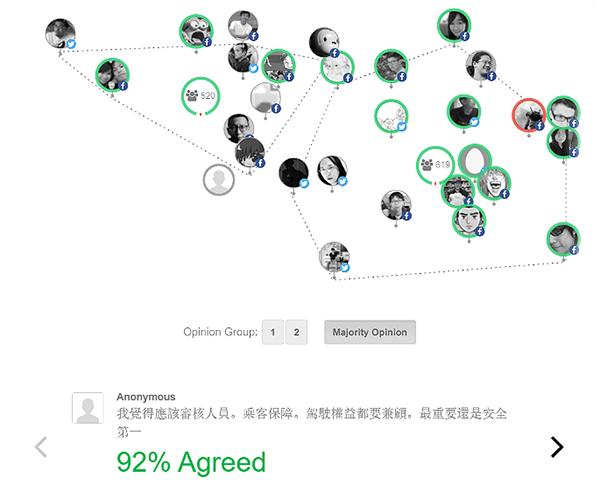

Other countries’ political parties cultivate greater participation methods. In 2016, Elizabeth Barry of the nonprofit Public Lab studied the vTaiwan process, spurred by the country’s 2014 Sunflower Movement, whereby proposals move from public online input to deliberation phases to a government policy making process. If a party in the U.S. were committed to such a process, its decision-makers like Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi would know that they can’t simply kill popular proposals on Big Tech antitrust action or congressional stock trading—that there exists another avenue for policies to become law. Last year, Taiwan’s Digital Affairs Minister Audrey Tang continued using the crowdsourced debate tool Pol.is to bring in views on emerging tech. More Democratic-led bodies could pick up Pol.is, g0v tools, the participation platform Decidim, or other software—the results could show that majorities of Democrats and the overall public in more congressional districts support an Israel-Gaza ceasefire.

A U.S. political party could demonstrate its commitment to democracy by adopting citizens assemblies, a practice of randomly-selected representative group meetings that good-government researchers have been tracking for years. If assemblies had been in place, their results widely publicized, establishment Democrats might have detected warning signs on economic well-being before losing the Electoral College in 2016, and might better gird themselves to pass socially-beneficial programs in the windows of government control they have.

Under the current Democratic Party leadership, state parties are unwilling—and under-funded—to experiment with such outreach programs to see if they increase turnout among disaffected voters. With far greater accountability on display, public trust in the political process, which has cratered, stands to grow. The real holdup, one imagines, is that the results of knowing what’s broadly popular and motivational to an infrequent voter might stand in stark contrast to their party’s governing record, which often listens to corporate lobbying interests and wealthy donors first. For more Democrats to understand what’s possible for liquid democracy in their state parties, sharing knowledge of how the establishment—like former President Obama—has weighed in heavily on their party’s leadership in backrooms is a start.